Economists, legislators, and Social Security advocates have long proposed strategies to increase Social Security’s revenue and slow our Trust Fund’s steady shrinking.

Each strategy has its benefits and drawbacks on its own, but combined thoughtfully into a comprehensive policy plan, we can create a long-term financial solution adding decades of solvency back to the program with the least possible negative impact on working Americans and retirees.

Over the years we have researched many of these strategies—consulting with financial experts, conducting policy surveys with both working and retired Americans, and compiling studies from outside organizations—arriving at what we feel is a policy plan that best restores long-term solvency while reflecting what our members most want to see in a comprehensive reform package.

Most importantly to us and our members, our plan does NOT rely on benefit cuts to restore the Trust Fund. Retirees—and those still in the workforce—have expressed time and time again they will NOT tolerate a Social Security reform plan that requires cuts to already inadequate Social Security benefits. And we absolutely agree.

Our plan consists of four strategies we’ve determined meet the requirements of what can be considered a significant or long-term solution to restore Social Security. These strategies are those we feel represent a bipartisan approach, the attitudes and desires of the beneficiaries for which we advocate, and our goal to achieve a fix that puts the least pressure possible on the least Americans.

Pay Back the Trust Fund

For decades, Social Security has collected contributions through the payroll tax to fund retirees’ Social Security benefits.

Many people may think the Social Security Trust Fund exists as a traditional savings account. But, though “trust fund” may imply a fund that holds cash assets, the Social Security Trust Fund does not. Instead, it functions more like a ledger than a savings account.

When payroll taxes are collected, most of that money is immediately used to pay current day retiree benefits. The federal government, seeing a growing retiree population on the horizon, has over-collected payroll taxes to build a surplus. Instead of steeply increasing payroll taxes on Americans to keep up with an aging population, the surplus was built gradually. The surplus was intended to provide benefits for a larger group of retirees without applying a large amount of tax pressure on future workers.

But there is no saved money in this country. There are always bills that need paying. The $2.85 trillion dollar surplus built over the years has been converted into Treasury notes, allowing the federal government to use it to fund countless things that need funding. Every single dime of payroll taxes is spent almost instantly, whether it’s on direct benefit payments or expenses entirely unrelated to retirees. The Trust Fund is just a running tab of how much money the government owes to retirees with interest.

We and our members are not supportive of this funding strategy. We believe money intended for Social Security payments should ONLY be for Social Security payments.

While these loans are backed by the full faith and credit of the United States—and the interest paid on this borrowing does go back into the Trust—there are some risks and consequences relying on bonds to pay retirees.

We have seen in recent years how budgetary disputes and unforeseen economic problems can put Social Security benefits at risk.

When payroll taxes are converted into Treasury bills, we have also seen how these bills are misrepresented as “debt” by those who find it politically expedient to attack the program. Social Security funds itself, but thanks to this system of constant borrowing and repaying, the program is often criticized for being the leading source of debt in our country. This opens the program up to be “reformed” in ways that are not fair or beneficial to the retirees who paid in.

Ultimately, we would like the surplus gradually restored by the U.S. Treasury and for the program to return to being a program funded by workers and used only by retirees. Social Security should be off-budget and NOT subject to scrutiny during debt and spending debates.

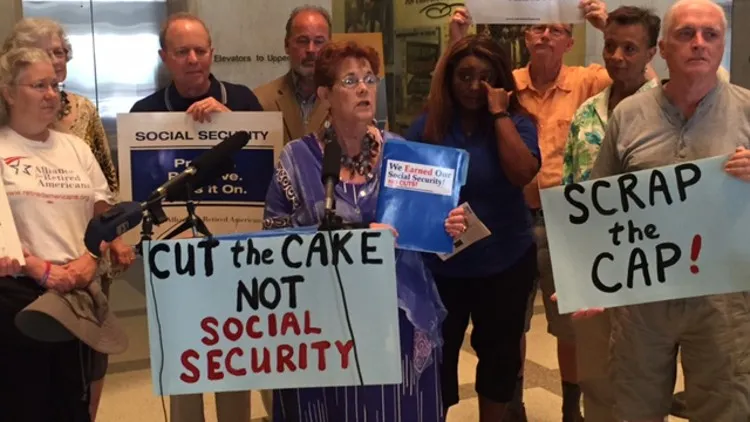

Scrap the Cap

This is, by far, the most popularly supported strategy to increase contributions to Social Security. The vast majority of both working and retired Americans support abolishing the income cap that prevents the wealthiest Americans from contributing to payroll taxes on all their income.

In an effort to create a payroll tax system that doesn’t unfairly ask a small amount of wealthy individuals to fund a disproportionately large portion of Social Security—especially considering there is a maximum benefit amount that may not be equivalent to a wealthy person’s lifetime contributions—legislators created an income cap. This cap kicks in after the first $147,000 a person makes.

This means anything a person makes after $147,000 is NOT taxable under FICA.

This tax cap has been part of Social Security since the 1930s.

But comparing incomes between the 1930s and the 2020s, we see a tax cap that has not kept up with an ever-increasing disparity between the wealthy and the middle class.

Around the time Social Security was put into law, there were only about 20,000 millionaires in the country. These days, there are over 200 million Americans who can call themselves millionaires (and over 700 of them are billionaires—the first ever confirmed billionaire in the United States was Henry Ford in 1925).

With a huge increase in the number of Americans making income far exceeding our current tax cap and a huge gap between the $50,000 income of the average American and 200 MILLION people making million-dollar incomes, the income tax is said by many to be regressive.

The income tax cap shields billions of dollars every year from being taxed to fund Social Security. Requiring all Americans to pay FICA taxes on 100% of their income—something most Americans already do—would provide a significant boost to Social Security’s coffers.

End the “Carried Interest Tax Loophole”

The maximum taxable wage cap isn’t the only tax loophole limiting Social Security contributions from the highest income earners.

Financial executives, like investment fund managers, include a very small number of extremely wealthy Americans who have an additional income tax shield on top of the maximum taxable wage cap.

Current tax law allows hedge fund managers to classify the bulk of their income as capital gains—not a salary. Income classified as capital gains is NOT subject to the income tax, but rather a much lower capital gains tax.

But even if the capital gains tax rate was equivalent to the income tax rate, capital gains taxes do not go toward Social Security. Capital gains, interest, and dividends are considered “unearned income.” Unearned income is not taxable by Social Security. Not a single cent of the billions of dollars being made by this very small group of people is going into Social Security.

In the much the same way as eliminating the income tax cap would increase contributions to Social Security, eliminating the carried interest tax loophole would create another source of revenue for the Trust Fund.