For every service, every business, every organization, and every program, there’s an administrative budget.

While most of an organization’s income is directed toward the product or service it provides to its clients, a portion of that income has to be used for daily operational expenses. These expenses include things like salaries, facility rent or maintenance, insurance, and supplies.

And although many people tend to criticize organizations–particularly governmental or charitable organizations–for their administrative

spending, without it, those organizations wouldn’t be able to function to serve their clients. How can a food bank serve the hungry if there’s no money to pay the electric bill, the water bill, or a staff to run it?

The Social Security Administration (SSA) is no different. Though most of its revenue goes toward paying the Social Security benefits of retirees, a certain amount must be put toward an operating budget and administrative expenses. Currently, that amount is nominal: less than a fraction of a penny on every dollar collected in payroll tax contributions.

No matter how much an organization shaves down its operational costs, there’s always going to be a bare minimum–no organization can operate for free. And as long as the SSA is spending any amount of money on something other than paying benefits, there will be plenty of people willing to criticize.

And then there will be some who will label that spending “waste” and suggest we make cuts to eliminate it.

When we talk about cuts to vital social insurance programs like Social Security, we tend to focus on direct cuts to benefits, like raising the retirement age or low or no cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs). Rarely are budgetary cuts to administrative spending the first thing that comes to mind. This is because we focus on payment of benefits as being the sole service provided by the SSA.

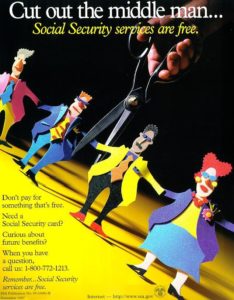

Although payment of benefits is the goal of the SSA, the actual services provided by the Administration are many, including:

- Handling new or replacement Social Security card applications

- Benefit filing

- Benefit application appeals

- Tax document filing for employers

- Providing knowledgeable speakers and materials for educational purposes

- Providing benefit statements for current and future beneficiaries

- Operating programs like Ticket to Work, a program to help disability recipients boost their earnings and find employment

To make sure the public can access these services, the SSA currently employs nearly 60,000 people at 1,230 field offices across the country.

Though costs per dollar are small, with so many employees and offices, operating costs add up. In 2015, the SSA collected $920.2 billion in payroll contributions. Of that sum, 96.3% went to Social Security beneficiaries and only 0.7% paid administrative expenses (approximately $6.4 billion).

That’s a pretty huge sum to most people, but a very small amount compared to what’s collected and given to beneficiaries. It’s because of this administrative spending that the overwhelming majority of what gets collected can end up where it belongs: in the pockets of retirees.

Still, those looking to reduce government spending often look to these operational expenses when the time comes to make cuts. And though citizens may find these kinds of cuts more palatable than direct cuts to benefits, nevertheless they amount to the same thing.

Already, cuts to the operational budget of the SSA have resulted in reduced staff, closed field offices, the elimination of paper statements, and extended the length of time it takes for an applicant to be approved for certain kinds of Social Security benefits. These changes not only directly affect benefits, but also hinder beneficiaries’ ability to access important information and programs offered by the SSA.

Sometimes, these cuts are made in the name of reducing “fraud” and “waste.” The reality is the SSA has done a tremendous job of limiting these problems already. Moving vital funding from the administrative budget to put more of an emphasis on fraud detection does more to remove funds from critical services than it does to reduce fraudulent claiming.

Ultimately, all of the services provided by the SSA to help Americans monitor and eventually file for their benefits are paid for by the payroll tax. Every contributor to Social Security is entitled to access and take advantage of these tools and services.

When that access becomes frustrating or limited because of budgetary cuts–access that YOU, an American worker, paid to have through your contributions–it’s really no different than any other Social Security cut.

Think about it: driving farther because your nearest field office was shuttered, waiting longer because the office doesn’t have adequate staff to handle your needs, waiting a year or more for a disability hearing, and waiting upwards of three weeks to replace a card or change your name.

All of these hold-ups cost time and money–time and money you shouldn’t have to spend since you already paid for these services.

So the next time you hear a legislator ruminate over cutting administrative expenses from the SSA (and from the already low 0.7% operating budget), consider what it could mean for your access to important Social Security services.

And consider that any cuts to the money you contributed to the Trust Funds–whether it be in the form of no COLA, reduced benefit checks, or unreasonably long waits at the SSA office for basic services–is a cut to Social Security.