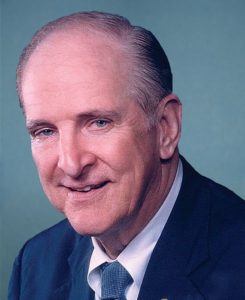

On December 8th, U.S. Representative and Ways and Means Social Security Subcommittee Chairman Sam Johnson (TX-3) unveiled the first of what is sure to be many Social Security reform proposals in the coming months, the Social Security Reform Act of 2016.

On December 8th, U.S. Representative and Ways and Means Social Security Subcommittee Chairman Sam Johnson (TX-3) unveiled the first of what is sure to be many Social Security reform proposals in the coming months, the Social Security Reform Act of 2016.

His legislation — a bill that proposes sweeping changes to everything from how cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) are calculated to phasing out the retirement earnings test and the benefit taxation of working or disabled seniors — signals the beginning of Social Security reform discussion in the 115th Congress.

In a press release, Johnson states “the Social Security Reform Act of 2016 puts Social Security back on a sustainable path by modernizing the program for the 21st century, rewarding retirees…for their years of work, and improving retirement security.”

The bill pays particular attention to strengthening Social Security for low-income earners, proposing raising the minimum benefit for lower income workers, allowing seniors to collect benefits without a penalty if they choose to keep working, and adjusting the way we calculate payments such that those most in need will benefit.

Chairman Johnson’s legislation accomplishes these goals without proposing any increase to the Social Security tax.

But opponents of the bill claim beneath the calls for increasing benefits for the most vulnerable seniors lay huge cuts that will devastate middle class beneficiaries — amounting to as much as a 30% reduction in benefits.

Among the biggest changes listed in the bill is raising the full retirement age from 67 to 69. While this is an oft-mentioned strategy to improve the solvency of the Trust Fund, critics note increasing the retirement age inflicts substantial benefit cuts to the nearly 50% of all retirees who retire early.

It could also widen the already sizable gap between the benefits of rich and poor Americans. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) indicated in a 2016 report that low-income earners have a life expectancy as much as 12 years less than the highest income earners. This means a worker earning $20,000 per year may lose as much as 14% of their lifetime benefit — and a worker earning $80,000 per year could gain 18% more by virtue of living longer.

Perhaps to combat this disparity, the bill proposes major adjustments to the COLA formula. Social Security COLAs for high-income earners would be reduced – and in some cases, eliminated completely. In contrast, COLAs for low-income earners would increase at a quicker rate. In addition, it requires that COLAs be calculated using the chained Consumer Price Index (CPI), a CPI that more accurately measures inflation in general.

But the chained CPI is calculated taking the spending habits and “market basket of goods” of all American consumers into account. It doesn’t factor seniors’ increased spending on healthcare with already limited buying power. To make matters worse, the chained CPI rises much more slowly than the regular CPI – meanwhile, the cost of healthcare typically rises faster than other necessities.

Though Chairman Johnson’s legislation is by no means a perfect fix, he admits that his is merely the first word in a larger discussion he hopes to have about Social Security reform in the near future:

“My commonsense plan is the start of a fact-based conversation about how we do just that. I urge my colleagues to also put pen to paper and offer their ideas about how they would save Social Security for generations to come. Americans want, need, and deserve for us to finally come up with a solution to saving this important program.”