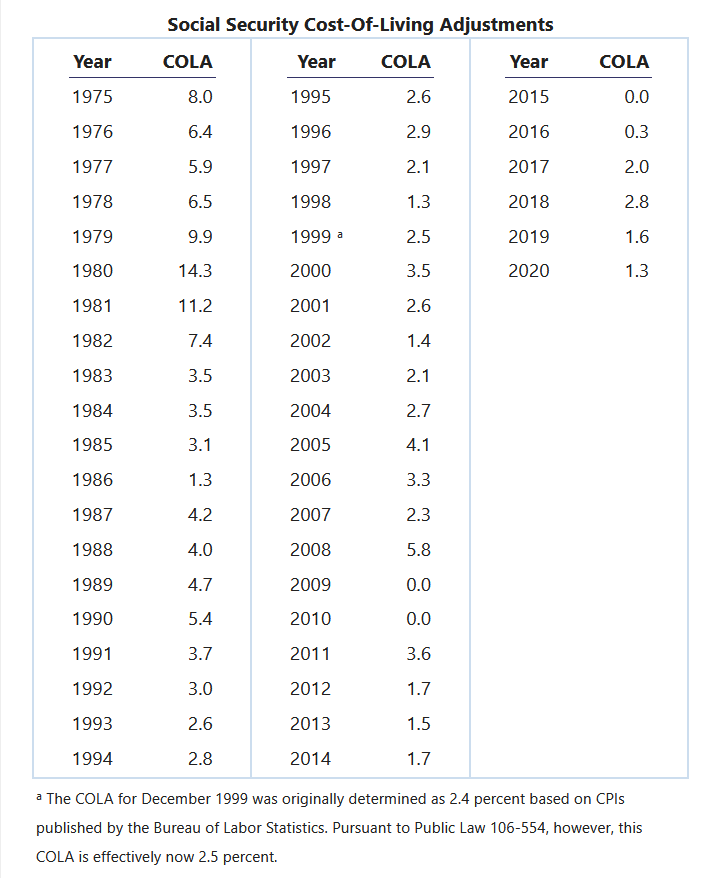

There’s no arguing the past ten years have given us the most consistently low Cost of Living Adjustments (COLAs) in the history of Social Security COLA increases. Only three times in the history of COLAs have we failed to receive any increase at all, and two of those times happened in past decade (the third happened in 2009, so we might as well count that one, too).

Presumably that’s because inflation has gone down this decade compared to previous years. COLAs are only issued when it’s determined prices for critical consumer goods have increased. The more these prices go up, the larger the COLA should be to account for it.

Now, find ONE Social Security beneficiary who will tell you their COLA has been even close to keeping up with the prices of the things he buys. Go ahead. We’ll wait, but we won’t hold our breath.

It would be easy for someone to argue retirees aren’t satisfied with their COLA increases because they just want bigger checks. Of course. No matter how well-off you are, we all know there’s absolutely no such thing as a “spare” dollar. We all want more money.

But the data is there for the Social Security critics if they want it. And that data says seniors know what they’re talking about.

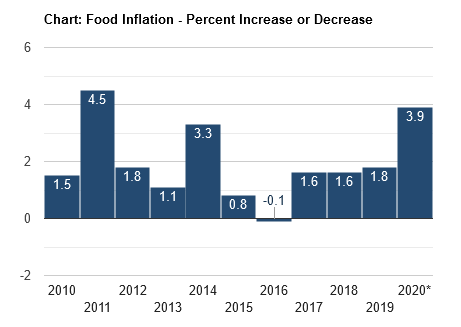

Let’s take a look at two key areas of spending for seniors: food and healthcare.

Isolating the costs of these items over time, we can see pretty quickly something isn’t right here.

U.S. Food Inflation

U.S. Healthcare Inflation

Right now grocery and health costs are at massive highs. And that comes as no surprise: thanks to the pandemic, food and health costs, specifically, have spiked with high demand, sluggish shipping, and shortages.

We also know the pandemic has obliterated the value of other critical consumer goods, like gasoline. It’s the net rise and fall in prices of all of these combined goods that ultimately produces the COLA each year.

But beneficiaries bemoaning low COLAs is nothing unique to the pandemic. Oil prices collapsing may explain a low COLA this year, but what gives every other year? We’re talking about ten years of steadily low COLAs while the prices of basic goods increase, especially healthcare.

On Tuesday, the Social Security Administration set the official COLA for 2021: 1.3%, among the lowest on record. This will add up to roughly $20 dollars extra for most beneficiaries. Twenty dollars a month would be perfect if all seniors were worried about is the ability to splurge on name brand orange juice and laundry detergent, but it isn’t. Seniors are worried about how they’re going to afford hundreds of dollars of critical medication every month on top of their mortgages and property taxes.

The real devil behind low COLAs is embedded deep within the calculation itself, and he’s there whether we’re living in a pandemic economy or not.

We’ve definitely already talked about the problems with using our current CPI-W to determine raises for seniors. And that’s certainly part of the problem. But what we want to take a look at runs even deeper than that. It’s a problem with the idea of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) itself.

Whether we continue to use a CPI focused on working Americans’ spending habits and buying power or shift to a CPI modeled on seniors’ spending, COLAs will still remain lower than we would like. That’s because the logic we use to to create the CPI is designed to keep those COLAs low.

There are two philsophies we’ve used to create the CPI and determine inflation. There’s the one we’re using now, the Cost of Living Increase (COLI) and the one we’ve used in the past, the Cost of Goods Increase (COGI). They may not sound all that different, but they’re actually radically different.

You see, the COLI is a measurement of how expensive it is to live in a certain area. It takes a really diverse amount of things into account, including measuring the quality of certain things against their rising prices. It also leans heavily on the idea that when offered a cheaper generic option for an item, consumers WILL choose to purchase the cheaper item. This is a pretty important detail, so keep it in mind as you continue to read.

The COGI, on the other hand, is exactly what its name describes: a pretty straightforward comparison of the costs of a market basket of goods from one year to the next.

Over time, we gradually shifted from simply looking at the cost of goods and looking at the cost of maintaining a certain standard of living. As we’ve drifted toward favoring a standard of living measurement, we’ve gotten pretty far away from a CPI that directly measures inflation. THAT’S where the problems started.

It’s a lot easier to see those problems when we look at some real life examples of the COGI and the COLI in action.

Let’s look at a few common household items: hand soap, steak, and televisions. These are items we probably all have in our homes (unless you’re a vegetarian, in which case, our apologies). And let’s say these items have risen in price:

A bottle of liquid hand soap: rose from $1.00 to $1.50

A package of filet mignon: rose from $15.00 to $17.00

A new 50-inch television: rose from $500 to $1,000

If we were evaluating these price changes from a COGI point of view, measuring the inflation here would be pretty simple:

Hand soap increased 50%

Filet mignon increased 13.3%

Televisions increased 100%

Averaged altogether, we have a 54.5% increase in the cost of these items. That’s some serious inflation.

Now lets apply COLI evaluation to these same items:

Hand soap increased 50%, but there are generic hand soap options available for $0.99. Since consumers are expected to purchase generic options when available, this would be detemined to be a 0% increase in price.

Filet mignon increased 13.3%, but cuts of steak that are comparable and less premium, like sirloin or skirt steak, are only between $6 and $10. Again, it’s assumed consumers will go for the cheaper option, and since they are still able to eat steak, there is no loss in “standard of living” as far as diet choice goes. This would be determined to be a 0% increase in price.

Televisions have increased 100%. Fair warning: THIS one is going to irritate you. On a lot of tech items and other “luxury” goods, there is another value assessment calculation that comes into play. It’s called the hedonic adjustment, and the purpose of that adjustment is to hold increases in quality against increases in price. What this does is evaluate how much of the increase in cost in the item is due to inflation or to technological or quality enhancement. Televisions may have gone up in price 100%, but maybe the new ones on the market are 4K smart TVs. This would be seen as a significant quality increase that would justify a price increase. So, again, this would be a 0% increase in price.

That’s how the cost of goods that rose 54.4% can be found to have increased 0% under the COLI CPI calculation. That is why COLAs never seem to rise at the rate of the goods we buy. Measuring the “cost of living” is not simply measuring a rise in prices. It is looking at rising prices under a few critical caveats: consumers will make substitutions to save, consumers have access to cheaper substitutions, and quality enhancements cost money. All of these caveats combined can obfuscate the reality of inflation.

But there are very legitimate reasons why assuming consumers will substitute is flawed. People in some areas might not have access to a diverse variety of generics and store brands. They also may need to stick to certain brands for whatever reason, especially regarding pharmaceuticals or special dietary items.

And let’s just be perfectly honest about one thing: anyone seriously suggesting someone who wants filet will sub in a sirloin and notice no loss in quality has the palate of a garbage disposal. What’s allowable as a reasonable substitution under this system is often comparing apples to oranges.

So, the reason COLAs are low is because of the very nature of evaluating inflation through a cost-of-living lens. It just simply isn’t an accurate way to gauge inflation, and in fact, usually does the exact opposite by painting a rosier picture than is reality for many people.

Add THAT to the fact that this is being done within a framework that looks at the buying habits of WORKING Americans—not retirees—and we end up with a really insufficient Social Security COLA situation for seniors.